by Admin | Anti-money laundering

The cost of money laundering and other forms of financial crime are critical to a bank’s future. Germany’s troubled Deutsche Bank faces fines, legal action and the possible prosecution of senior management because of its alleged role in a $20bn Russian money-laundering scheme, according to a recent report in The Guardian.

Money laundering scams included shell firms lending money to each other and then declaring themselves bankrupt. On top of the heavy fines that can be incurred, the damage to brand and reputation can be incalculable. Deutsche Bank has been dubbed the “Global Laundromat”, with the total funds involved estimated at around $80bn.

Now, there’s a big challenge for any PR company that’s up for it.

And yet the cost of being squeaky clean (at least, in the eyes of the regulator) is also eye-watering. In the US alone, the cost of AML compliance is estimated at $23.5 billion per year. European banks come close with $20 billion spent annually. And for what? The banks identify a measly one percent of all the money being laundered.

In Europe, that amounts to just $10 billion of the $1 trillion that is being laundered. Which is just half of what is being spent on compliance! Even more shocking, over the last decade, 90% of European banks have been fined for AML-related offences; globally, banks have been fined approximately $26 billion over the last 10 years.

So, what is the point of “compliance”? It has become an end in itself, a tick-the-box exercise that is imposed by governments and regulators and keeps thousands of compliance professionals in highly paid jobs, and tens of thousands of low-paid drudges doing soul-destroying menial work.

Anti-money laundering has always been, and remains, a largely manual exercise that involves chasing up cases of unusual or suspicious activity, which in the overwhelming majority of cases turns out to be a false positive.

At the root of the problem are the four Vs of Big Data: The accelerating rate of growth in the volume of financial data in circulation, its velocity of circulation, its variety and variability. According to the International Data Corporation (IDC), 44 Zettabytes of data will have been generated by 2020.

To put that in perspective, a zettabyte is one billion Gigabytes. A Zettabyte is equal to one sextillion, or 1021. The number of grains of sand on Earth is estimated to be a far smaller number, just 7.5 * 1018, or even quintillion, five hundred quadrillion grains.

Therefore, talk about needles in haystacks comes nowhere near to describing the challenge! Trying to find a single criminal transaction is more akin to finding one grain of sand across several continents. But with an additional complicating factor.

The number of grains of sand on Earth, though vast, is finite. Whereas we are constantly pumping out more financial data. By 2030 there will be some 50 billion electronic devices connected to the internet, most of them generating transactions in one form or another.

There is only one way to escape from this cul-de-sac, and that is through the application of technology.

Let’s consider some of the technologies involved. Specifically, technology that is powerful enough to trawl through those mind-bogglingly vast oceans of transactional data, detecting patterns that indicate criminal activity with a very reliable degree of probability.

True, there is a lot of IT hype out there but if you are serious about knowing your customer and tackling money laundering with an acceptable return on your efforts and investment, you need to acquaint yourself with artificial intelligence (AI).

Not a day passes without us hearing about artificial intelligence, and it all sounds amazing but do we really know what hides behind artificial intelligence?

The AI idea started at the beginning of the last century. More specifically, the first scientific paper written by Walter Pitts and Warren McCulloch on the subject influenced the important Dartmouth conference in 1956.

AI has a broad definition. It applies to any form of intelligence demonstrated by computers and similar devices. The Financial Stability Board defines AI as “the theory and development of computer systems able to perform tasks that traditionally have required human intelligence.”

Machine learning (ML): This is a key sub-field of AI and it is developments in machine learning that have powered many of the recent successes of AI in the finance sector. It refers to the science of algorithms and statistical models that computer systems use to perform specific tasks without using explicit instructions. Typically, the more historical data that a machine learning system has, the more it learns how to respond to new data.

Machine learning is categorized into two groups Supervised and Unsupervised learning:

Artificial Intelligence and Machine learning uses two types of techniques: Supervised, models are trained on data with known inputs and outputs (also known as categorized data) to identify potentially suspicious transactions. while Unsupervised, models are exposed to raw data to find hidden patterns or intrinsic structures that might signal money laundering or other financial crimes.

Everything is becoming “Smart” such as our cars, mobile phones, televisions, watches, even are cities. Nevertheless, we have not yet lived in the age of unsupervised AI. Its counterpart supervised AI already exist.

Applying AI and ML in the fight against financial crime

Two primary benefits for the banks engaged in combating financial crime: mainly the reduction of false positives and building more sophisticated risk profiles based on behaviour, rather than relying only on rules, will go a long way to increasing the efficiency in the AML process.

The methodology behind traditional transaction monitoring systems is essentially, rules, thresholds and risk profiles based on industry specifics such as product, geography, and transactional value and type.

As we have seen, this is not the most sophisticated nor the most efficient approach when trying to detect suspicious activity which has lead to a high-volume of false positives.

Therefore, the future of transaction monitoring means being able to dive deeper into transactional data in near real-time as opposed to only using a library of set rules based on industry specifics.

The importance of this is demonstrated with the use of supervised learning in sanctions screening where every payment transaction must be screened to check if any beneficiaries are on a sanction or pep list.

However, these screening systems produce a lot of false positives that must be dispositioned by a human reviewer, before the transaction can leave the gateway. Hopefully, AI can be trained, well enough, to eventually takeover much of the task of reviewing these false positives.

Artificial intelligence could not have came at a better time and you simply cannot afford not to experiment with it, especially for a under-resourced medium or small sized bank. AI and ML have game-changing potential through there ability to provide a means to scale and adapt to the modern threat of financial crime.

That said, artificial intelligence is not, and probably never can be, a substitute for human intelligence. In order to better explore and realize the potential of AI, banks must understand its limitations and risks as well as its capabilities. Essentially,

AI’s role is to support the non-automated and semi-automated tasks processing and investigating huge amounts of data that human beings simply cannot handle. In short, AI can and must help where there is lots of historical data, from which algorithms can learn, and the risk of making a mistake is small.

Risk Profiling

The current challenge is that these customer category do not consistently represent groups of entities with consistent transaction behaviour. As a result, when alerts are generated on good customers, financial institutions will need to decide on either tweaking the rule for the entire customer category or create a new customer sub-category. For this reason, many banks are working with over 200 sub-categories, literally losing the oversight.

Therefore, an area of promise for AI could be risk profiling and customer segmentation. AI analysed transactions, would place customers in more relevant risk segments based on their behaviour. For example, one customer segment could be entities that engage in large cross border wire credit transactions, have high-frequency counterparties, and a large number of unique originators.

If a customer executed transactions outside of the normal parameters for their segment, they would be subject to further analysis, including, potentially, investigations by humans. This would minimize the number of false positives while increasing the productivity and lowering the cost of compliance.

Humans on the other hand will need to step in where there is little information (or the information has already been sifted and condensed) but the risk of making a mistake is significant.

Here are the challenges to Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning that nobody talks about:

- Data access and labeling – ensure that you have access to robust data that is labeled properly to avoid “garbage in, garbage out,”

- Explainability – regulators expect that you can describe how your ML model works. Otherwise, just a “black box”

- IT infrastructure – needs to be able to maintain high availability in order to accommodate spikes in demand for the ML model.

- Potential bias – the training data does not accurately represent the population or the training data is influenced by prejudice.

This means that while investigating how to deploy AI it is also vital to establish a system of governance and an ethical framework through which the development and use of AI can be governed. AI systems will need to be continuously assessed to determine the quality of their outcomes, and constantly improved if the financial services industry is to keep pace with the ever-changing nature of financial crime.

However, appealing that this technology might sound to the people watching the bottom-line. The reality is that AI systems require months of laborious training, as experts must feed vast quantities of well-structured data into the system for it to be able to draw meaningful conclusions and those conclusions are only based upon the data that it has been trained on.

In short, human learning is every bit as important as machine learning!

You can find more articles as well as contribute your own articles to the AML Knowledge Centre here on LinkedIn by joining the group @ https://www.linkedin.com/groups/8196279/ or visit or page on cryptocurrencies https://aml-knowledge-centre.org/cryptocurrencie

by Admin | Anti-money laundering

Maybe I am just getting old, but it came as a shock that Bitcoin has now been around for a decade. Yes, it was launched in January 2009. Early in its existence, financial authorities became concerned that, due to its semi-anonymous and decentralized nature, Bitcoin would become the currency of choice for money laundering and illegal weapons trade, financing of terrorism and drugs trafficking.

Yet it is only lately that governments and regulators have put in place systems and regulations to ensure that AML and KYC are applied to cryptocurrency accounts.

Try to get an answer to the question, “How many cryptocurrency users are there?” and you soon see why they have a problem on their hands. According to Bitcoin there are 7.1 million active bitcoin users. But a staggering 32 million bitcoin wallets had been set up by December 2018. Coinbase, the cryptocurrency exchange, has 13 million users. Last year, Ethereum claimed to have overtaken Bitcoin in terms of active users. And there are literally hundreds of other cryptocurrencies, with widely divergent business models. Moreover, users in emerging markets barely figure in the statistics and could run into millions.

The legal status of these currencies varies enormously from one regulatory regime to another, further confusing the issue.

Back in 2017 the European Union took limited measures requiring exchanges and wallet providers to carry out KYC and AML checks on customers and any beneficial owners, i.e. requiring them to collect, process and record personal data and to share these with public authorities. But the requirements only applied to exchanges that allow the exchange of cryptocurrencies against regular fiat currencies, effectively excluding many popular cryptocurrencies.

2018 then saw the release of the Fifth AML Directive in the EU, which created tougher regulatory obligations for crypto exchanges. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) will also be releasing specific international AML standards for crypto companies later this year. Cryptocurrency companies will therefore need to become as serious about maintaining AML compliance as traditional banks.

Three camps

When it comes to regulatory compliance, the crypto world seems to fall into three camps.

It is inevitable that the more responsible crypto companies will welcome the regulatory embrace: they realize that regulations are necessary in order to keep expanding their market, and to protect reputation. These are the “must haves”.

At worst, criminal activity could bring the whole crypto market crashing down, so many other companies will understand that they cannot avoid regulations and will have to deal with them. This is the view of the “necessary evil” camp.

However, a significant number of crypto exchanges are doing everything in their power to avoid having to introduce KYC. Ethfinex’ Trustless DEX launched in September 2018 without KYC, insisting that it is impossible to obscure the source of a person’s funds: every transaction is visible and recorded forever on their blockchain. Hodl allows traders to swap cryptocurrencies without the need to undergo compliance. These companies form the “violation of privacy” camp.

And there is still a long way to go. A recent study by PAID discovered that even in the US and EU, two-thirds of cryptocurrency exchanges fail to comply with even the most basic KYC requirements. They ask for nothing more than an email address and a phone number, which means they know virtually nothing about their customers.

According to the most in-depth report so far, carried out by the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance in 2017, there is a huge divergence between the different types of wallet providers: “All wallets providing centralized national-to-cryptocurrency exchange services perform KYC and AML checks. The preferred KYC and AML methods are internal checks, which are in some cases complemented with traditional third-party KYC/AML service providers. Third-party blockchain analytics specialists are only used by 17% of wallets performing KYC/AML checks. All small wallets performing KYC/AML checks only do so internally.”

Cryptocurrencies will face similar challenges to banks

But for legal and regulatory reasons, crypto exchanges will be increasingly obliged to perform KYC, like it or not. In doing so they will soon run into the same problems and challenges faced by conventional financial institutions: long waits for clearance and an increasing number of time-consuming false positives.

Moving forward, if cryptocurrencies are to be adopted into the mainstream, both blockchain technology companies and crypto platforms will need to do a couple of things:

First, they must take a seat alongside the regulators in charge for a new solution.

Second, they need to get involved with multi-stakeholder use cases that examine the specific nature of anti-money laundering and other financial crime using cryptocurrencies. This will help build reputation and sideline the bad guys.

Third, they need to engage with consultants providing KYC/AML services and technology that meet their needs.

If they take these steps, the cryptocurrency exchanges can do a lot for their cause. The fact is, many traditional financial institutions use outdated technology to run their AML programmes, leading to high levels of false positives, which in turn causes friction during onboarding and payment processing and increases operational costs. The crypto exchanges can gain a competitive advantage by becoming early adopters of the latest automated technologies to transform their KYC and AML procedures.

Paul Hamilton

Go to the AML Knowledge Centre LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/groups/8196279/ to read more articles on AML and financial crime. Also, we look forward to your input!

by Admin | Anti-money laundering

The European Commission’s fifth Anti-Money Laundering Directive entered into force on 9 July 2018 and Member States have until 10 January 2020 to transpose the majority of its provisions. Its main aim is to establish a centralised public register of companies and their ultimate beneficial owners, thereby reducing the number of shell companies. It was an important step forward in combating money laundering by criminal enterprises.

The UK government has confirmed it will implement this latest Anti-Money Laundering Directive before it leaves the EU. It said that it will transpose the new rules into law as the deadline for adoption, January 2020, falls within the post-Brexit implementation period that was agreed in principle between UK and EU towards the end of 2019; however, that agreement has been rejected by the UK parliament. What now happens when the United Kingdom departs from the European Union is therefore a serious concern.

The UK has in fact put its own legislation in place (in May 2018) to be able to deal post-Brexit with both sanctions and money-laundering under the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018 (“SAMLA 2018”). The main provisions of SAMLA 2018 will come into force in 2019. The purpose of SAMLA 2018 is to ensure that once the UK has left the EU that it can continue to impose, update and lift sanctions provided for by the United Nations (“UN”) and pursuant to other international obligations, and effectively detect and prevent money-laundering and terrorist financing by implementing internationally recognised standards. Under this regime the UK has already adopted its own particular approach in some respects e.g. sanctions (in the form of an asset freeze) may be adopted on individuals by description rather than by specific name.

Some commentators have warned that by stepping outside European regulatory and policing arrangements, Britain is at risk of becoming Europe’s money laundering capital. Money launderers often seek out areas where there is a low detection risk due to weak or ineffective AML policies and a breakdown in international cooperation. A disorderly exit from the European Union could therefore provide the perfect opportunity for money launderers to take advantage of potential loopholes and uncertainty.

For example, at present, the UK is a member of Europol, the European Union’s law enforcement agency. Europol has a remit to tackle European-wide serious and organised crime threats, and much of its work involves anti-money laundering efforts. In addition to providing an arena in which joint action can be organised, Europol also maintains a Europe-wide criminal information and intelligence database, the Europol Information System (EIS). The EIS collates the national databases of all twenty-four-member states, making them searchable by all Europol members. If, for example an investigation was being conducted into British nationals in France, the French police would be able to check whether they had been connected to crime which had taken place elsewhere on the continent.

Each year, the UK uses this database for around 250,000 searches relating to terrorism and crime investigations. If the UK, like Canada or Norway, were accepted as a third-country member, Britain would no longer have full access to the data, could no longer run operations from Europol, and would have less influence. It would be possible to have a special agreement, such as the EU negotiated with the United States, to give the United States greater access to data, but it is unclear how long this would take.

There is perhaps an upside. It is likely that the EU could engage in such a flexible special solution while pursuing security areas where the UK has resisted greater European integration. But in the meantime this loss of shared intelligence will greatly hinder the ability to combat illicit flows, as British officials will be unable to “follow the money trail” once it has left their locality.

Last year the EU together with the European Banking Authority (EBA) announced measures to combat white collar crime, which will ensure that Europe’s banking supervisor is the ultimate meditator when it comes to money laundering. The EBA has been given the authority not only to address problems at banks but also to perform risk assessments and further develop AML standards.

What this means for UK and European banks

In December, the EBA issued a warning to European banks that they must step up their efforts to mitigate the risks of a disorderly Brexit. The EBA warning reflected the real risks that will arise if the UK finds itself excluded from policy-making on money laundering and white-collar crime in general. As things currently stand efforts depend greatly upon cooperation and collaborative international treaties which the UK may be forced to leave. The UK will have to align its own anti-money laundering standards with those set by global leaders, such as the United Stated or the EU. The UK’s proximity to the EU and its existing financial relationships suggests that the UK may have to adopt EU standards, as European-wide compliance will be necessary for post-Brexit interaction. However, like most other EU-related matters, the UK will no longer be in a position to influence them, so its ability to combat money laundering could be curtailed. Criminals are likely, for example, to exploit the redesigned customs setup that follows Brexit.

With the UK eliminated from existing agreements and the customs union, British and European banks will be more reliant on working cooperatively at the international level and investing in their own know-your-customer (KYC) technology if they want to remain on top of the challenge. A lot have already been planning for the worst-case scenario, but this is not such an easy call for smaller banks.

For many international banks, customers may need to be transferred to the EU. The need to on-board many customers creates an opportunity for unsafe accounts to slip through the net and gain legitimacy, or alternatively if the process is delayed, this could result in bottlenecks and backlogs that lead in turn to significant losses in revenues and market share. This will not be a “one-off” event but may endure over some period of time as the implications of Brexit unfold fully. Less well-resourced financial services entities would be wise to investigate cost-effective technology (e.g. cloud-based) solutions and put processes in place to avoid the worst from happening.

Go to the AML Knowledge Centre LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/groups/8196279/ to read more articles on AML and financial crime. Also, we look forward to your input!

Picture:

lazyllama – Shutterstock

by Admin | Anti-money laundering

Transparency campaigners dismayed at clean bill of health for UK government

On Friday, 7 December the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), a G7 initiative to combat money laundering and terrorist financing awarded the UK the highest rating it has ever given. The move was greeted with stark disbelief by anti-corruption and transparency campaigners such as Global Witness, Transparency International and Corruption Watch. They have a point. Many would echo their view that while the UK has taken a number of initiatives to combat money laundering in recent years, the flow of dirty money continues unabated.

A Global Witness campaigner stated, “Hundreds of billions of dirty pounds are washing through our banks and property market every year, as the government openly admits. Giving it so much credit before we’ve seen real change makes a mockery of the whole process.” Transparency International has often expressed the view that the FATF approach is fundamentally flawed. It is all too cosy. According to its January 2017 position paper: “Policy discussions within the confines of a largely closed, expert-driven anti-money laundering (AML) space have not generated sufficiently effective AML policies. No country is yet compliant with the international FATF standards.” The paper calls for greater openness and the involvement of civil society. Let us, however, add some context. As FATF rightly stated in announcing its report, the UK is the largest financial services provider in the world and, as a result of the exceptionally large volume of funds flowing through its financial sector, the country also faces a significant risk that some of these funds have links to crime and terrorism.

The FATF report emphasizes that the UK government has a strong understanding of these risks and has implemented a raft of policies, strategies and proactive initiatives to address them. It states that the UK aggressively pursues money laundering and terrorist financing investigations and prosecutions, achieving 1400 convictions each year for money laundering. And it adds that the UK’s overall anti-money laundering and counter financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) regime is effective in many respects. Nevertheless, when it comes to the shortcomings, FATF’s criticisms of UK efforts are ultra-cautious. It says that “the intensity of supervision is not consistent across all [financial and non-financial] sectors and UK needs to ensure that supervision of all entities is fully in line with the significant risks the UK faces.” It adds that the UK “needs to address certain areas of weakness, such as supervision and the reporting and investigation of suspicious transactions. However, the country has demonstrated a robust level of understanding of its risks, a range of proactive measures and initiatives to counter the significant risks identified and plays a leading role in promoting global effective implementation of AML/CFT measures”

The Global Laundromat

So where are we to find the truth between these extremes? We believe that there is truth in both positions, but neither the optimism (some would say complacency) of FATF nor the “demands” for “tougher action” of the campaigners can offer a comprehensive answer. It is true that the United Kingdom has had some spectacular successes in recent months. An example was the clampdown on Scottish Limited Partnerships (SLPs).

According to the Wall Street Journal, these “are used by thousands of legitimate businesses, including the private-equity and pension industries, bringing more than £30 billion ($38 billion) a year in investment to the UK”. However, SLPs have also been an important conduit for dirty money and especially Russian dirty money, including $20 billion in a scandal known as the Global Laundromat. The UK responded with new laws in 2017 to make their ownership more transparent and claims that this has led to an 80% drop in the number of new registrants. In July of this year, the UK also laid out a broader set of proposals requiring foreign companies and other legal entities owning UK real estate to reveal the true beneficial owners.

But these measures received a lukewarm welcome by Global Witness and other campaigners who pointed to the lack of prosecutions, demanding that the authorities make better use of the information it receives from both financial institutions and non-financial institutions (e.g. legal practices).

Technology must be better employed

Sifting through information to identify the ultimate beneficial owners behind ghost companies is no easy matter. In the 2014 KPMG Global AML Survey, respondents stated that “identifying complex ownership structures is the most challenging area in the implementation of a risk-based approach to KYC collection”. Part of the problem is that thousands of offshore operations and others with a complex ownership structure are perfectly legitimate, so how does a bank or a lawyer identify those that are being used for fraudulent financial transactions, without scaring away business? They need to be extremely careful to distinguish between what’s legit and what isn’t. Many businesses use sophisticated legal structures for valid reasons such as asset protection, estate planning, privacy and confidentiality.

Technology has become essential to help financial institutions and their legal partners to better understand and document ultimate beneficial owners, identify suspect activities and decide the appropriate level of due diligence required. Basically, the whole industry is banking (no pun intended) on big data, machine learning (ML), and artificial intelligence (AI) to help simplify complex processes and automate repetitive tasks. Even though, these buzzwords have become a hot topic many don’t even know the difference between the two and use the terms interchangeably. ML refers to a computer system that has the ability to learn how to do specific tasks, in contrast, AI enables computer systems to perform tasks done by humans. While AI can replace some rudimentary tasks, I wouldn’t say that compliance analysts are one of them. Therefore, by applying these technologies, the compliance staff would have more time to deal with non-routine events and complex cases as well as having better information through a cleaner, more traceable process to make objective decisions.

Of course, machine learning models can process tremendous amounts of data, but ML systems still need to learn the difference between a false positive and a false negative and that in real-time. First, there simply isn’t enough well-structured data available at most financial institutions that can be used for teaching these ML / AI models. IBM’s Watson, named after a Sherlock Holmes character, has learned this hard way. As with every new technology wave CRM, Business Intelligence, and Predictive analytics, etc. tech companies can’t wait to sprinkle these terms on every bit of their software like fairy dust. Of course, consulting firms are the biggest advocates who can’t wait to implement such solutions!

As of June 2017, the Watson AI platform had been trained on six types of cancers which took years and thousands of medical doctors.

Second, bad actors are always adjusting and trying new schemas and third, the financial services landscape is continually changing leaving ML and AI platforms with a real-time knowledge gap. However, appealing this technology might sound to the people watching the bottom-line. The reality is that ML / AI platforms require months and in many cases years of laborious training, as experts must feed vast quantities of well-structured data into the platform for it to be able to draw meaningful conclusions and those conclusions are only based upon the data that it has been trained on.

- Learning transaction behaviour of similar customers

- Pinpointing customers with similar transactions behaviour

- Discovering transaction activity of customers with similar traits (business type, geographic location, age, etc.)

- Identifying outlier transactions and outlier customers

- Learning money laundering, fraud, and terrorist financing typologies and identify typology specific risks

- Dynamically learning correlations between alerts which produced verified suspicious activity reports and those that generate false positives

- Continuously analyzing false-positive alerts and learn common predictors

For the most part, financial crime will be driven by advances in technology and this marriage of regulation and technology is not new, in itself. However, with the continual increase in regulatory expectations, the staggering levels of cyber-attacks against financial institutions and the FinTech disruption makes RegTech the perfect partner.

In brief, RegTechs address many gaps in today’s financial crime program by improving automation in the detection of suspicious activity, which would be a significant move from monitoring to preventing financial crime while being more cost-effective and agile!

However, financial institutions have been done this path before putting their faith in technology but this time they would be wise to thoroughly start with small-scale pilot projects. Financial institutions need to invest in data quality as it is a key component of any successful financial crime program. High-quality data leads to better analytics and insights that are so important to accurately teaching ML and AI models but also drive better decisions. Therefore, transparency campaigners would do well to campaign for the adoption of such technological solutions. These will provide the infrastructure needed to meet their demands and enable the change they seek.

Written by

Go to the AML Knowledge Centre LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/groups/8196279/ to read more articles on AML and financial crime. Also, we look forward to your input!

“Top Misconceptions of Cryptocurrency as a Payment System”

by Admin | Cryptocurrency

The early 21st century might very well go down in the annals of history as the gold rush of the modern age. Utility and security tokens are emerging from all corners of the globe and project teams are licking their lips as a new wave of investor funding is born. Capital from Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) in 2018 has already surpassed the 4x mark compared to 2017. And we’re only just moving into the second half of the year.

Tokenization of assets existed well before the invention of Bitcoin or even the arrival of the Internet. But now they’re taking their place at the forefront of the next digital revolution. For better or worse, the Ethereum project has popularized token creation through its ERC20 standard. Why build your own blockchain when an off-the-shelf solution already exists?

The Nitty-Gritty – What is a Token?

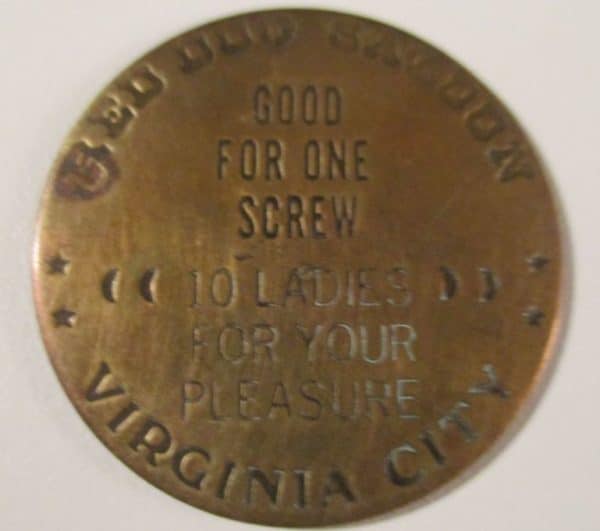

The only difference between a token and the spare change you carry in your wallet is where you can use it. Coins issued by national authorities and governments are considered a legal tender for everyday life and can be exchanged widely. Tokens, on the other hand, are usually issued by a private company for use in a local network.

A great example (that probably brings back childhood memories) is the tickets issued at your neighbourhood funfair. And of course, what article would be complete without a real-world wild west example:

A token used in the Red Dog Saloon brothel

Jokes aside, it should be apparent then that there are no strict rules when defining a token. You could issue your own family token from rocks in your yard. As long as you could get others to buy into the idea, a family tradition of rock tokens could theoretically take off.

In the cryptocurrency space, it’s utility and security tokens which have arrived first to the party.

Utility Tokens

Just as listed in the examples above, tokens represent access to a company’s product or service. In the case of ICOs, companies often don’t have a product or service available upfront and are looking for funding. By offering tokens in exchange for capital, projects are making investors a promise of a future product/service. The investor is taking on the risk that the project will have a usable token sometime in the future of the proposed network. And hopefully, that token will have appreciated in value.

We already see this model in action in the video game industry. Companies will offer ‘early-access’ benefits to video game fans willing to fund development for their next big title. Often these fans will receive bonuses in the form of game skins, behind-the-scenes content, in-game currency, and so on.

Security Tokens

Here’s where things start to get a little fuzzy. The crypto community would be more than happy to have every token regarded as a utility. In that case, they could simply get down to the business of investing without big brother hanging around. Governments and authorities, on the other hand, still view any investment that aims to make a profit as a security.

In a July 2017 testimony in front of the US Senate, SEC chairman Jay Clayton had the following to say about virtual currencies:

Merely calling a token a “utility” token or structuring it to provide some utility does not prevent the token from being a security. Tokens and offerings that incorporate features and marketing efforts that emphasize the potential for profits based on the entrepreneurial or managerial efforts of others continue to contain the hallmarks of a security under U.S. law.

The showdown is real. Fortunately, it’s a lot less bloody than it used to be. Two projects positioning themselves in the regulated token space are Polymath and tZERO. They are well worth checking out.

The Tax Man Cometh

The arrival of the SEC into the cryptocurrency arena is a rather controversial one. On one hand, the completely unregulated ICO market is creating a tremendous opportunity for risk-taking entrepreneurs looking to make a real difference. On the other, just about anyone and their grandmother is setting up shop online with a few bucks and clever marketing hype.

Some level-headed guidelines to direct projects, keep investors safe, and stay decentralized are sorely needed.

You know what they say, nothing is certain except death and taxes!

The Howey Test

The US Supreme Court created the Howey Test in the 1940’s to evaluate whether a transaction qualifies as an investment. By doing so, the SEC and other US authorities have a benchmark to determine what a security is and what requirements are needed under US law. Securities in the US need to be registered with the SEC.

Under the Howey Test a transaction is considered an investment if:

- It is an investment of money.

- There is an expectation of profits from the investment.

- The investment of money is in a common enterprise.

- Any profit comes from the efforts of a promoter or third party.

The obvious problem with this approach (for US authorities anyway) is that cryptocurrencies by their very nature cross international borders. Trying to regulate projects based completely in the US may work. But regulating projects in another jurisdiction or regulating globally distributed teams is another matter altogether.

Utility and Security Tokens: Closing Thoughts

Most observers of the current ICO craze would agree that some kind of regulation is needed to reduce the rising risks in this wild west of the digital age. At the same, it’s worthy to note that allowing a highly centralized authority like the SEC to regulate a decentralized network is highly suspect.

The SEC itself has come under fire in recent years, particularly in the wake of the 2008/9 economic crisis. Multi-billion dollar companies like Airbnb and Uber have delayed their public IPO listings due to, amongst other reasons, incredibly high listing fees. This illustrates that the SEC seemingly promotes a system which benefits the rich under the guise of accredited investing. Shutting out the common man from investing in the future will only drive them to continue with their reckless investing practices.

The answer, as usual, lies somewhere in the middle. Since decentralization is the theme of the cryptocurrency era we must assume, no, encourage that appropriate regulation will come not from the hands of wealthy special interests but from the cryptocurrency community itself.

This article was originally published on Coincentral.

Author:

Ryan Smith

“Top Misconceptions of Cryptocurrency as a Payment System”

Which can be read on Amazon Kindle Unlimited for Free You can find more interesting articles by visiting us on one of the following platforms: AML Knowledge Centre (LinkedIn) or Anti-Bribery and Compliance at the Front-Lines (LinkedIn)